In this position paper, the authors argue that high-stakes, standardized assessments place an enormous challenge both on learners for whom English is a Second Language and their teachers. Yet, based on a thorough review of the literature and their own recent research on standardized test preparation practices for English Language Learners, they also claim that employing culturally and linguistically responsive instructional strategies may lessen the stress associated with test-driven instruction and improve student learning outcomes as well.

Both the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act of 2001 (2002) and the impending implementation of the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) across the United States place high expectations on all learners. The CCSS were developed by the National Governors Association Center for Best Practices and the Council of Chief State School Officers to provide clear expectations for all students to equip them with the necessary knowledge and skills for college and career readiness (Common Core State Standards Initiative). Currently, the standards have been formally adopted by 44 states. The challenge of meeting the new standards is especially severe for English language learners (ELLs) for a number of compelling reasons: (a) special emphasis is placed on informational texts across all content areas, (b) college and workplace readiness are emphasized, and (c) no special accommodations are made for ELLs.

Abedi and Dietel (2004) claimed that at least four critical issues need to be considered when ELLs' participation in standardized assessments is compared to that of their native-English-speaking counterparts:

- Low ELL performance on state assessments and lower rates of improvement across several years have been documented.

- Instead of content attainment only, when it comes to ELLs' performance on state assessments, both content-based achievement and language ability are measured.

- The ELL population as a subgroup is highly transient; many high-performing ELLs leave the group.

- Numerous nonschool-related factors also impact on the group's performance.

Further, as a result of her extensive research on current assessment practices, Menken (2006) suggested that high-stakes testing impacts not only work with ELLs but also educational practice in general, noting that "standardized tests become de facto language policy when attached to high-stakes consequences, shaping what content schools teach, how it is taught, by whom it is taught, and in what language(s) it is taught" (p. 537). In addition, Valli and Buese (2007) suggested that "high-stakes policy directives promote an environment in which teachers are asked to relate to their students differently, enact pedagogies that are often at odds with their vision of best practice, and experience high levels of stress" (p. 520).

Because standardized assessments and standards-based instruction are expected to continue to define the educational landscape (Wiliam, 2010), we researched effective approaches to standardized test preparation for ELLs (Giouroukakis & Honigsfeld, 2010). Specifically, we conducted a multicase study to investigate the impact of high-stakes testing on the literacy practices of teachers of high school ELLs in three Long Island, New York, school districts in one of the most racially and socioeconomically segregated regions of the United States. The goal of the study was to explore what kinds of literacy tasks and materials were implemented in order to develop ELLs' literacy skills and prepare them to be successful on the New York State Regents English examinations required for graduation. Our findings indicated that the participating teachers engaged in both (a) instructional activities and materials that directly prepared their students for the state's high-stakes exam (teaching to the test) and (b) culturally and linguistically responsive practices. Based on these findings, we suggest that educators working with ELLs in all content areas and at all grade levels utilize culturally and linguistically responsive techniques in all their instruction, including when they engage their ELLs in test-preparation activities.

Key Concepts Defined

Cultural responsiveness and linguistic responsiveness have been previously defined by numerous researchers, the former receiving decades of support in the professional literature, and the latter becoming more widely researched in recent years. Culturally responsive teaching, according to Gay (2000), uses "the cultural knowledge, prior experiences, frames of reference, and performance styles of ethnically diverse students to make learning encounters more relevant and effective for them..... It is culturally validating and affirming" (p. 29) and thus invites students to become more engaged in learning. We concur with Lucas, Villegas, and Freedson-Gonzalez (2008), who defined linguistic responsiveness as involving

three types of pedagogical expertise [teachers should have]: (a) familiarity with the students' linguistic and academic backgrounds, (b) an understanding of the demands inherent in the learning tasks that students are expected to carry out in class, (c) and skills for using appropriate scaffolding, (p. 367)

It is important to note that both Gay's and Lucas et al.'s definitions include the prerequisite of teachers' understanding and affirmation of students' cultural and linguistic identities, which are "shaped by self-perceptions, desires, hopes, and expectations, as well as salient aspects of the social context, such as sociopolitical ideologies, histories, and structures that are often beyond the control of an individual" (Lee & Anderson, 2009, p. 181). Such identities are also impacted by "the various ideologies, power structures, and historical legacies associated with different forms of language use, cultures, and situations" (Lee & Anderson, p. 181).

Our Position

The NCLB Act (2002) requires ELLs to be included in high stakes tests (Irby et al., 2010; Coltrane, 2002). When English learners are included in state assessments, their academic performance is measured by tests that were designed for English-speaking students and, as such, may be culturally and linguistically inappropriate for ELLs. Test items may contain concepts or ideas that may be unfamiliar to ELLs who come from diverse cultures and who have not lived in the United States for a long time (Coltrane, 2002). For example, a prompt that asks students to write a persuasive essay about whether or not the United States should spend money on alternative energy sources will pose a challenge for ELLs who need to be familiar with a number of cultural references, such as the history of energy use in the United States, what alternative sources of energy exist, the views on this topic of the country's major opposing political parties, and the risks and benefits of spending resources on alternative energy versus oil drilling.

Teaching to the test as an all-too-common instructional approach may be especially damaging to ELLs whose cultural and linguistic needs may be overlooked as they may be exposed to "less meaningful instruction and a lack of focus on the sociocultural context in which students are schooled" (Collier & Thomas, 2010, para. 5). "[T]he vast majority of high-stakes tests are written and administered only in English, often leaving ELLs at a disadvantage and raising questions as to how the test results should be interpreted" (Coltrane, 2002, para. 4). Thus, based on our own as well as others' research (Gay, 2000, 2002; Giouroukakis & Honigsfeld, 2010; Menken, 2006; Moll, Amanti, Neff, & Gonzalez, 1992; Valli & Buese, 2007), we believe that when teachers implement culturally and linguistically responsive instructional practices, they pay special attention to the students' individual needs as opposed to teaching merely the mandated curriculum or to preparing simply for typical test items that appear on standardized assessments.

Implications for Instruction

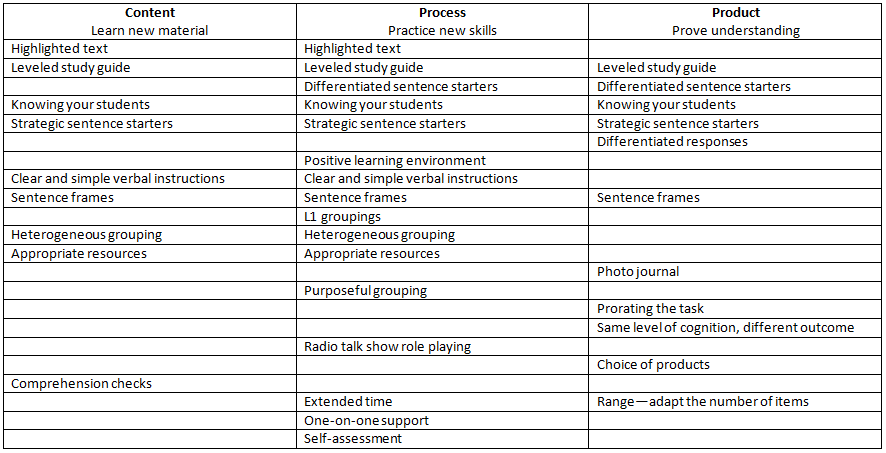

In response to the cultural and linguistic challenges that high-stakes tests pose for ELLs, we found in our professional experiences as teacher educators and staff developers and in our research that educators who successfully work with ELLs carefully craft their lessons to incorporate a variety of culturally and linguistically responsive strategies that (a) are closely aligned to the target curriculum; (b) consider the specific academic, linguistic, and social-emotional needs of diverse students; and (c) systematically and meaningfully support learning for ELLs. We provide teachers of ELLs with the following advice regarding culturally and linguistically responsive practices for ELLs based on our most recent research (Giouroukakis & Hongisfeld, 2010; Honigsfeld & Giouroukakis, 2011).

Culturally Responsive Practices

1. Incorporate content topics and instructional materials and resources that are relevant to students' diverse home cultures.

- 2. Relate to and validate ELLs' out-of-school, lived experiences by addressing local issues and current events embedded in the taught curriculum.

- 3. Use a variety of motivational techniques that allow students to engage with the curriculum in authentic and personally meaningful ways.

- 4. Embrace your ELLs' "funds of knowledge" (Moll et al, 1992) and allow them to show their expertise (rather than deficiencies) in the classroom.

- 5. Expand your ongoing, formative assessments to include authentic, performance-based, project-based, or task-based assessment tools. Rather than relying on outcomes from one measure, give students multiple opportunities to demonstrate their content and linguistic knowledge.

Linguistically Responsive Practices

1. Use chunking by breaking down challenging academic tasks to make learning manageable. Offer step-by-step linguistic modeling through think-alouds, read-alouds, and write-alouds.

- 2. Provide adequate wait time for students to process and respond to questions and prompts.

- 3. Create ample opportunities for oral rehearsal of new skills through small-group interactions and other cooperative group structures.

- 4. Modify reading assignments, worksheets, and both in-class and homework assignments by simplifying the linguistic complexity.

- 5. Use students' native language for clarification and to teach dictionary skills.

- 6. Introduce key testing vocabulary and sentence structures unique to standardized tests.

Conclusion

The demographics of U.S. schools continue to change and include increasing numbers of ELLs who have unique cultural and linguistic needs. Nevertheless, educators spend an increasing amount of instructional time on standardized test preparation, and policy makers continue to neglect what research (Abedi & Dietel, 2004; Collier & Thomas, 2010; Gay, 2000,2002; Ladson-Billings, 1995) indicates about best instructional and assessment practices for ELLs. Instead, we believe that teachers and administrators must advocate culturally and linguistically responsive practices that will recognize, value, and affirm ELLs' diverse backgrounds and unique academic needs. By utilizing curriculum and instructional practices that include students' different backgrounds, educators create opportunities for advancing ELLs' achievement on tests and ensuring academic success for all learners.

References

Abedi, J., & Dietel, R. (2004). Challenges in the No Child Left Behind Act for English-language learners. Phi Delta Kappan, 85, 782-785.

Collier, V. P., & Thomas, W. P. (2010). Helping your English learners in spite of No Child Left Behind. Teachers College Record. Retrieved from

http://www.tcrecord.org/content.asp?contentid=15937

Coltrane, B. (2002, Nov.). English language learners and high-stakes tests: An overview of the issues. Center for Applied Linguistics, Retrieved from

http://www.cal.org/resources/digest/digest_pdfs/0207coltrane.pdf

Common Core State Standards Initiative. (2010). About the standards. Retrieved from

http://www.corestandards.org/about-the-standards

Gay, G. (2000). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Gay, G. (2002). Preparing for culturally responsive teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 53(2), 106-116.

Giouroukakis, V, & Honigsfeld, A. (2010). High-stakes testing and English language learners: Using culturally and linguistically responsive literacy practices in the high school English classroom. TESOL Journal, 1,470-499.

Honigsfeld, A., & Giouroukakis, V. (2011, Spring). The ABCDE's of standardized test preparation. Idiom, 41(1), 3, 23.

Irby, B.J., Fuhui, T., Lara-Alesio, R., Mathes, P. G., Acosta, S., & Guerrero, C. (2010). Quality of instruction, language of instruction, and Spanish-speaking English language learners' performance on a state reading achievement test. Texas American Bilingual Education, 12(1), 1-42. Retrieved from

http://tabeorg.ipower.com/main/images/stories/2010journal/ journals/Quality_of_instruction.pdf

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research, 32, 465-491.

Lee, J. S., & Anderson, K. T. (2009). Negotiating linguistics and cultural identities: Theorizing and constructing opportunities and risks in education. Review of Research in Education, 33,181-211.

Lucas, X, Villegas, A. M., & Freedson-Gonzalez, M. (2008, July). Linguistically responsive teacher education: Preparing classroom teachers to teach English Language Learners. Journal of Teacher Education, 59, 361-373.

Menken, K. (2006). Teaching to the test: How No Child Left Behind impacts language policy, curriculum, and instruction for English language learners. Bilingual Research Journal, 30, 521-546.

Moll, L. C, Amanti, C, Neff, D., & Gonzalez, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory into Practice, 31,132-141.

No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, 20 U.S.C.A. § 6301 et seq. (January 8, 2002).

Valli, L,, & Buese, D. (2007). The changing roles of teachers in an era of high-stakes accountability. American Educational Research Journal, 44, 519-558.

Wiliam, D. (2010). Standardized testing and school accountability. Educational Psychologist, 45, 107-122.

~~~~~~~~

By Andrea Honigsfeld and Vicky Giouroukakis

Andrea Honigsfeld, Ed.D., is a professor at Molloy College, Rockville Centre, NY. A member of Alpha Pi chapter (NY), she is the author or coauthor of numerous publications on teacher collaboration, coteaching, differentiated instruction, and other effective strategies for English Learners. ahonigsfeld@molloy.edu

Vicky Giouroukakis, Ph.D., is an associate professor of English Education and TESOL at Molloy College, Rockville Centre, NY. Her research and publishing interests include standards and assessment, cultural and linguistic diversity, adolescent literacy, and teacher education. vgiouroukakis@molloy.edu

Source: Delta Kappa Gamma Bulletin, Summer2011, Vol. 77 Issue 4, p6, 5p

Item: 508475770